What makes us human after

all? MODU’s design process is grounded in three core values: indoor urbanism, second nature, and public floor.

Indoor Urbanism

Indoor urbanism envisions buildings with fewer boundaries, with architecture at the intersection of two contrasting scales—the urban and the interior. Increasingly, activities traditionally associated with indoor spaces are taking place in outdoor urban environments. Simultaneously, interiors reflect the open-ended nature of cities. Together, these shifts encourage a reimagining of the environmental thresholds that connect architecture, cities, and interiors.

Second Nature

Second Nature reconsiders the cities and landscapes as

extensions of each other, imagining them as interconnected, hybrid realms. It

also encourages unlearning long-held spatial habits to adopt new ways of living

with the environment—both of which are a form of second nature. These new

habits are not based on separation but rather on making less distinction

between constructed spaces and natural ecosystems.

Public Floor

The public floor is active, ephemeral, and

dynamic. Experiences on this ‘floor’ are constantly changing—whether on a

city’s sidewalks, in its lobbies, streets, shops, or parks. Daily social

interactions unfold between members of the public. The interior realm is

reconsidered as an integral part of the city, shaped by the activities that move

through it, making it inherently more inclusive.

MODU conducts design-led research to

develop innovative strategies of climate adaptation for our cities and beyond.

Self-Cooling Walls

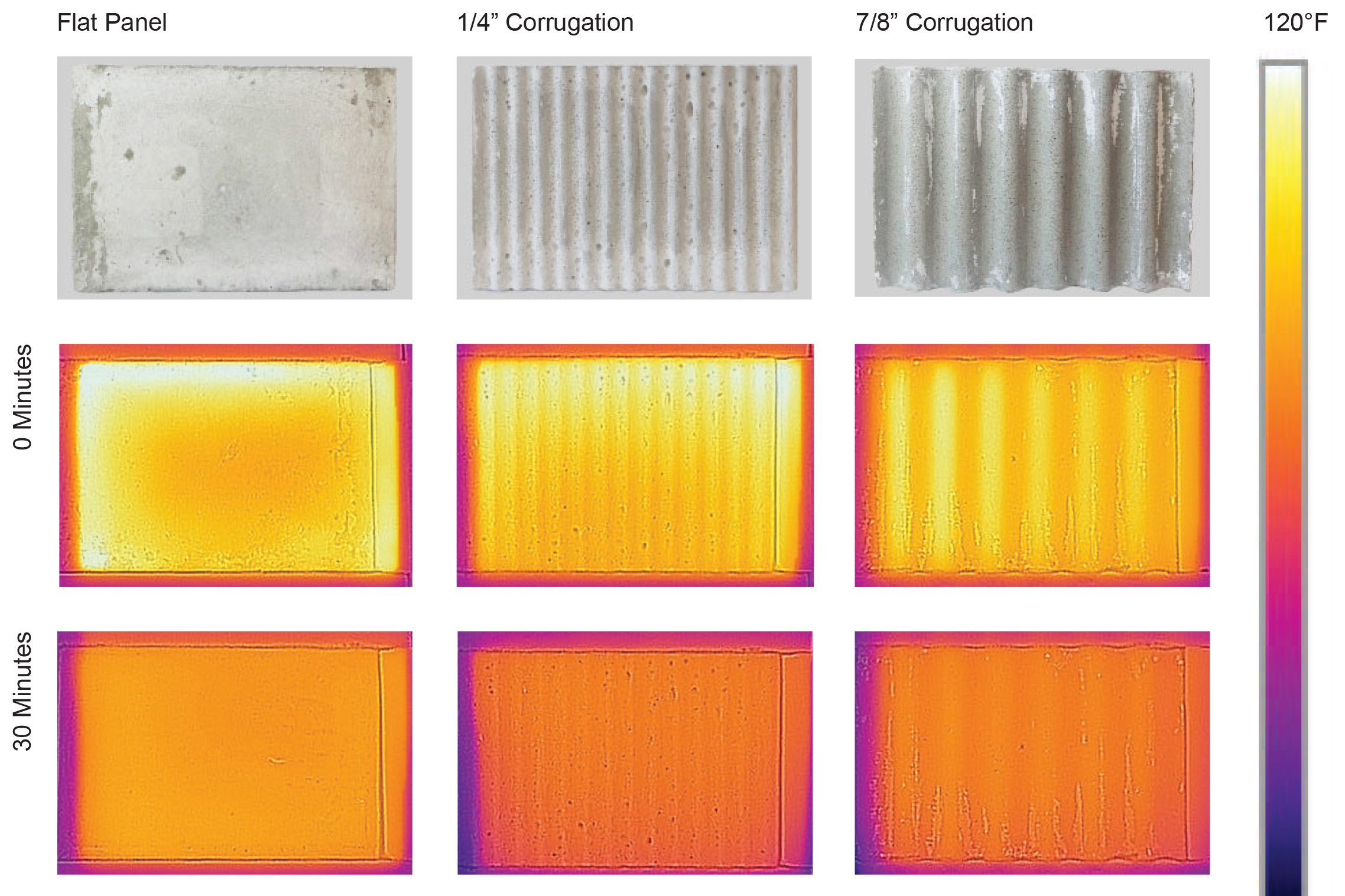

In Houston’s hot climate, self-cooling concrete walls are cast with

corrugation patterns that help release solar heat more rapidly when passed over

by wind. Research demonstrated varying cooling rates based on the patterning,

with a significant difference compared to flat, non-corrugated panels.

More intricate patterns are used on walls exposed to direct sunlight

to enhance self-cooling. The increased surface area of the corrugations, along

with transpiration from abundant plants, helps create more comfortable

microclimates. These passive design strategies improve human experience and environmental impact while

contributing to a distinctive visual expression.

More information here

Indoor Terrace

New York City’s hot summers and cold winters make a multi-season room

especially beneficial, open during temperate seasons and enclosed air-tight otherwise. An

indoor terrace creates a unique environment that evolves with the

seasons. Shaded during warm weather and featuring large openings, the indoor

terrace passively cools the air

before it enters the

building, lowering energy costs .

Radiant heating provides warmth in early winter, allowing for extended use. In the summer, plantings and natural breezes

help lower temperatures, promoting healthy indoor-outdoor living.

More information here

Coral Footings

Public installations typically generate significant amounts of

construction waste, which ends up in landfills. However, they can be designed

for recycling or reuse from the outset. In Miami, a steel structure was left

unpainted to facilitate recycling, while concrete footings were donated to an

artificial reef program.

The footings were cast with a network of holes for future marine life

and concrete textures specifically designed to promote coral growth. After

de-installation, the footings were lowered to the seabed to form the artificial

reef.

More information here

MODU launches initiatives to design for better futures. We work as creative entrepreneurs, engaging proactively with new ventures.

Horizontal City

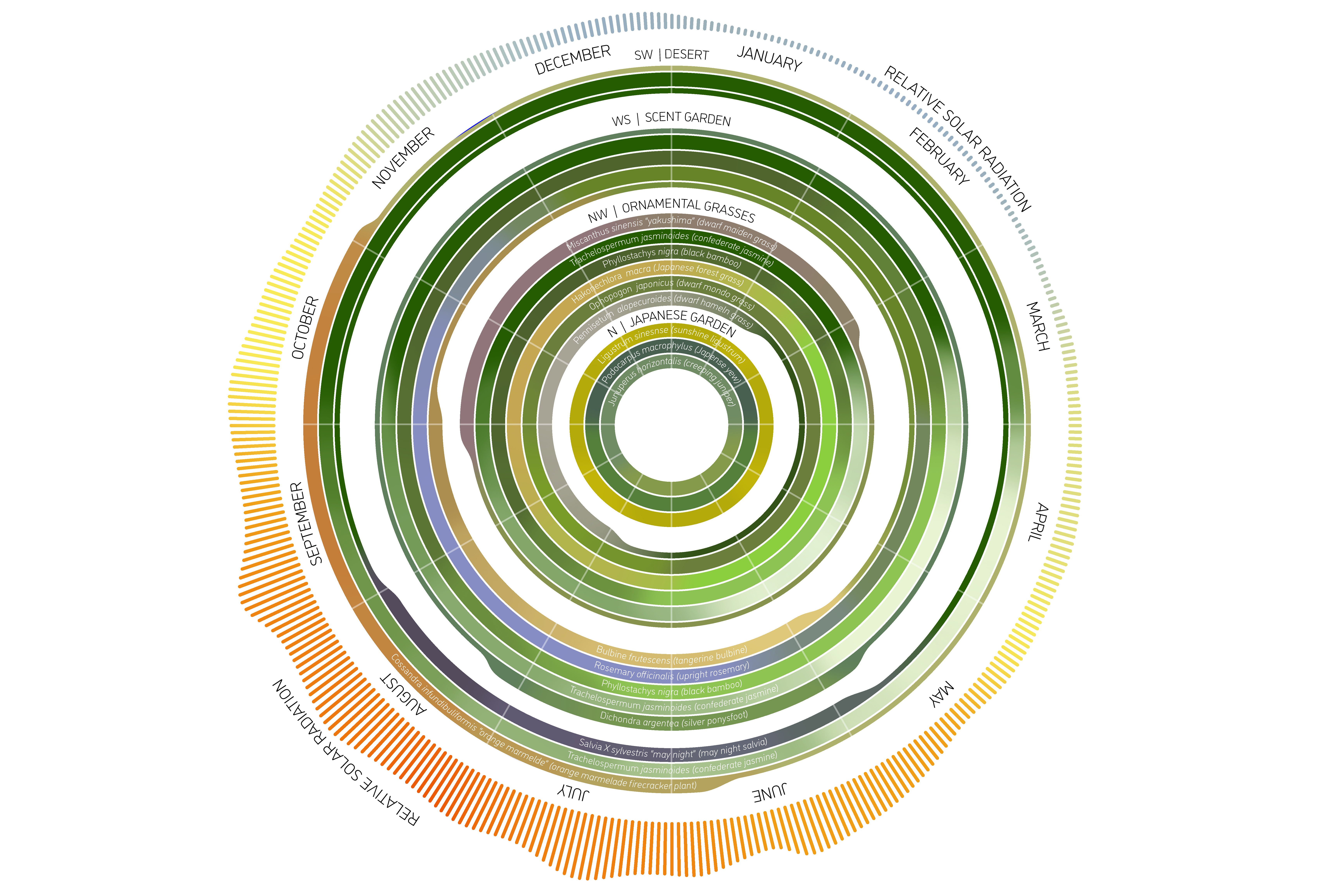

Research on the horizontal city shifts emphasis from New York’s

vertical identity to highlight its public floor. Mapping the city’s sidewalks

and streets documents the seasonal shadows cast by permanent structures, like buildings

and trees, and temporary ones, such as the private outdoor dining structures

prompted by the pandemic.

Invisible boundaries reveal vast inequities in shade: higher-income

neighborhoods have cooler micro-climates, with surface temperatures at times

thirty degrees less than lower-income areas. Highlighting these environmental

boundaries underscores the importance of more accessible outdoor comfort and urban

shade.

More information available.

Second Life

Second Life consists of “mini-buildings”: free-standing, modular

structures that adapt to different sites, whether within a building or in an

open lot. These structures activate overlooked assets in neighborhoods—sites

that are indoors, outdoors, or even in-between—revitalizing

properties while building communities. Our cities face a persistent problem: there

is an abundance of underutilized spaces at the same time as there is an urgent

need for affordable and adaptable spaces.

Each “mini-building” can be modified, creating unique visual

identities for businesses and community organizations. They

are rapidly assembled and can be relocated to other sites. They also utilize modular

elements to optimize assembly, requiring less time and lower costs than typical

construction projects. As a result, they require fewer time-consuming building permits

and reduce operating costs. Every Second Life site can be passively heated or

cooled “off the grid,” enabling them to adapt to changing environments.

More information available.